Are you sure you want to reset the form?

Your mail has been sent successfully

Are you sure you want to remove the alert?

Your session is about to expire! You will be logged out in

Do you wish to stay logged in?

Please note that you will need to be logged in with access to Bloomsbury Design Library to view the content featured below

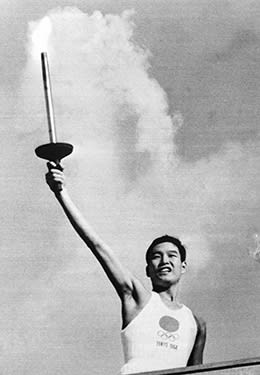

Yusaku Kamekura (1915-1997) was a hugely influential figure in post-war Japanese graphic design. His work for the 1964 Tokyo Olympics, particularly his bold, photographic posters, are globally recognized and were pivotal in defining Japan’s national visual identity throughout the Games. Kamekura was born in Niigata Prefecture, Japan and later studied at the Institute of New Architecture and Industrial Arts in Tokyo. Inspired by the Art Deco posters of A. M. Cassandre and Russian Constructivism, he went on to produce an array of designs including posters for the Expo ’70 in Osaka (an overview of the first world’s fair in Asia is given by Clive Edwards in his article in The Bloomsbury Encyclopedia of Design). Perhaps Kamekura’s most profoundly moving work was his poster, the first in the Hiroshima Appeals series, featuring flaming, falling butterflies. In 1978, he established and served as president of the Japan Graphic Designers Association (JAGDA) until 1993. As Sonoko Monden writes in The Bloomsbury Encyclopedia of Design, Kamekura was a pioneer who significantly raised the reputation of graphic design in Japan. He died in 1997.

Althea McNish (1924-2020), whose life and work spanned two centuries, was a highly influential textile designer known for her vibrant, colourful contributions to the British textiles industry. McNish was born in Trinidad, moved to London in the 1950s and, accomplished in art, fashion and textiles, went on to design fabrics and furnishings for Liberty, Dior, Heal's and Hull Traders. She was one of the first designers of African-Caribbean descent to achieve international recognition and her unique aesthetic and sense of colour can be seen in memorable designs such as Golden Harvest, Painted Desert and Grenada. Many of her designs are widely recognised today. In ‘Althea McNish and the British-African Diaspora’, in Pop Art and Design, Christina Checinska interviews Althea’s partner, John Weiss, discussing her work and her enduring influence in the industry.

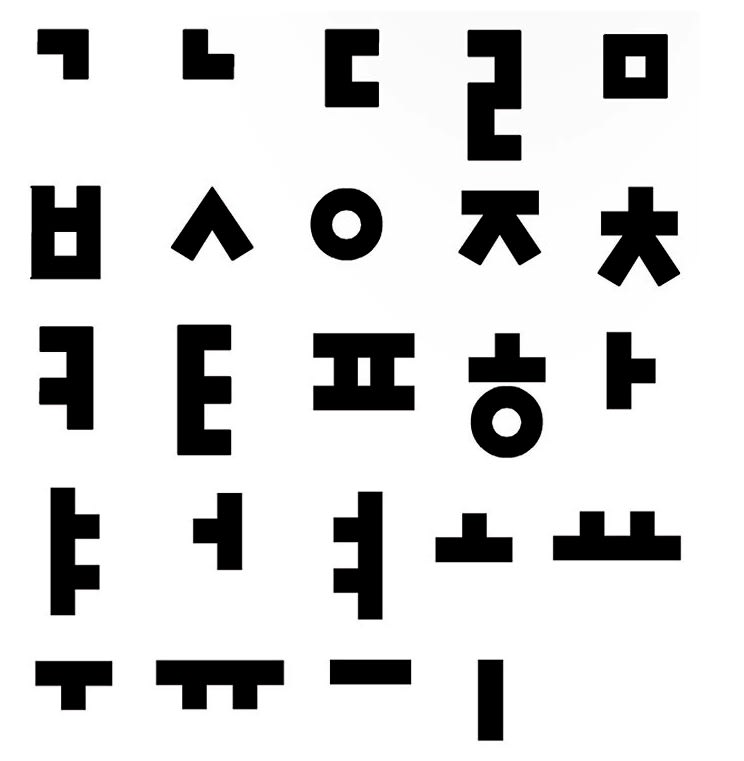

Korean graphic designer Sang-soo Ahn is best known for his development of four major Hangul (Korean alphabet) fonts, including the Ahnsangsoo Font in 1985. Read more about Ahn’s life and work in Yunah Lee’s overview in the Bloomsbury Encyclopedia of Design, and understand his work in the context of South Korean communication design in Chae Lee’s article in the Encyclopedia of East Asian Design.

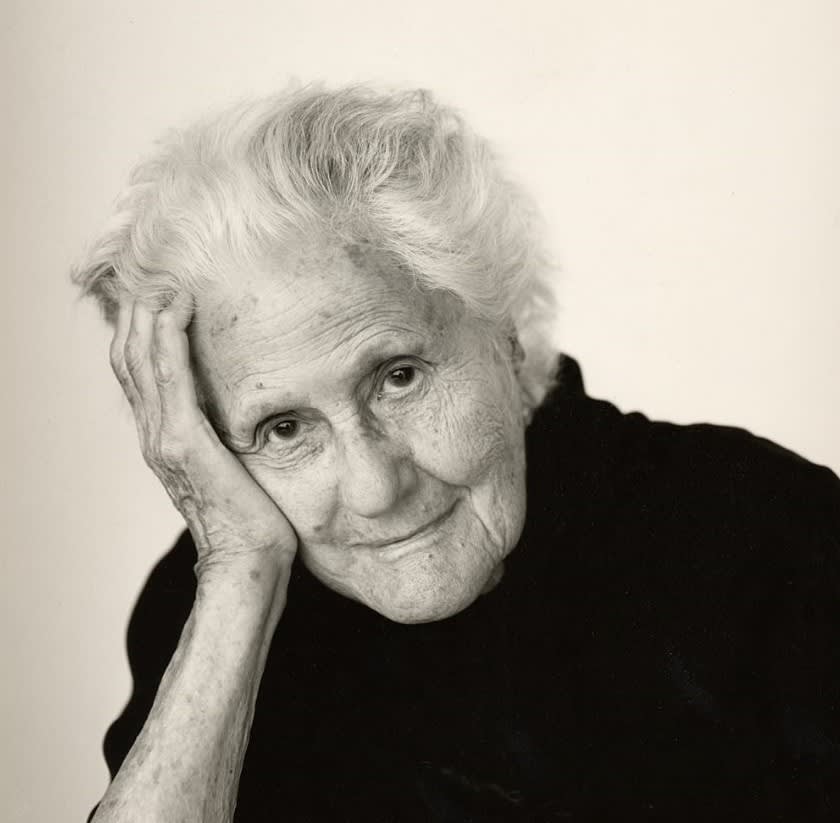

The Hungarian-American industrial and ceramic designer Eva Zeisel was born in 1906. She was the first female potter to train in a Budapest craft guild, and lived in both Germany and Russia before spending 16 months in a Soviet prison, on the false charge of plotting to assasinate Stalin. Once freed from prison and living in Vienna, she was again obliged to leave her country of residence, this time because of the growth of the Austrian Nazi Party, and she fled to London and then New York with her new husband, Hans Zeisel. In the US Eva re-established herself as a designer, teaching at the Pratt Institute and presenting an exhibition at MoMA. Zeisel lived in the US until her death in 2011, aged 105. Read more about Zeisel's life and work in the Bloomsbury Encyclopedia of Design.

One of the twentieth century's most influential architects and design educators, Walter Gropius founded the Bauhaus in 1919. Read an overview of his career from the Bloomsbury Encyclopedia of Design and extracts from his foundational writings 'Theory and Organisation of the Bauhaus' and 'Bauhaus Dessau: Principles of Bauhaus Production'.

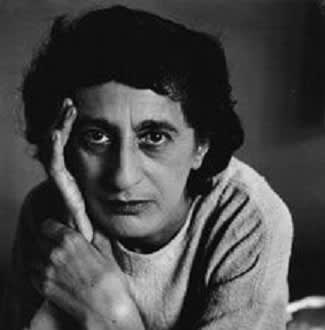

Anni Albers was a German-American weaver and textile designer. Born in Berlin in 1899, she went on to study at the Bauhaus. Discouraged from taking certain classes, Albers enrolled in the weaving workshop and made textiles her key form of artistic expression. After marrying Josef Albers in 1925, she wrote and taught at the Bauhaus for several years; you can read her article 'Design: Anonymous and Timeless' in our series of Critical and Primary Sources. The Albers emigrated to the United States when the Nazis came to power in Germany, taking up posts at the newly-created Black Mountain College. Anni Albers' creative practice, and her promotion of weaving, had a profound and long-lasting impact on American textile design.

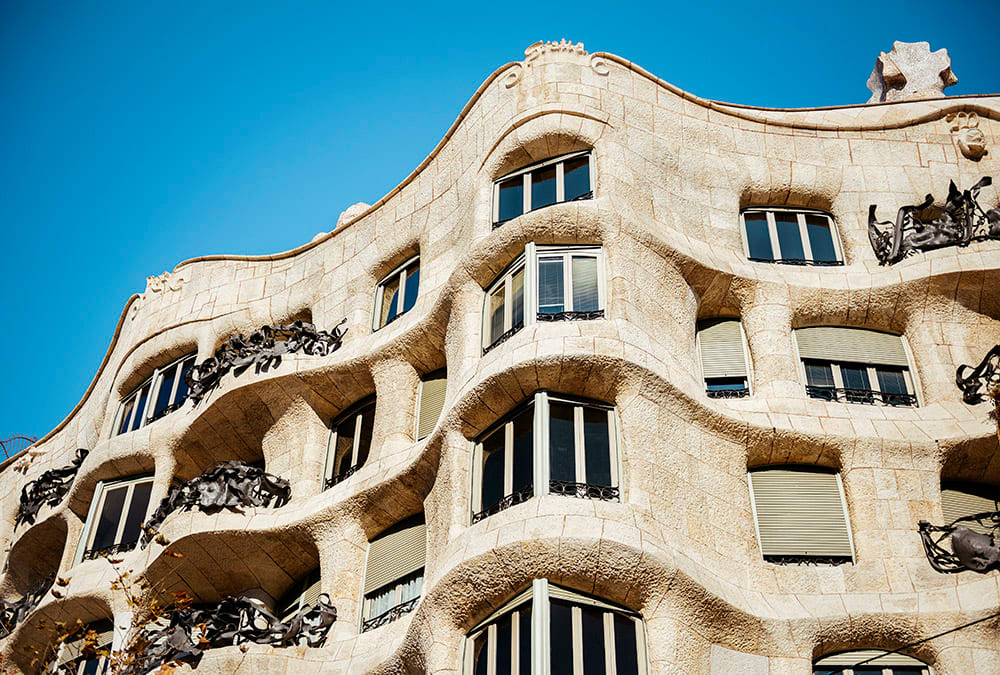

Gaudí's most famous works include Casa Milà (pictured here), Casa Batlló and Park Güell, though the Sagrada Família is widely considered to be his greatest masterpiece. You can read about Gaudí's unique take on Art Nouveau in Clive's Edwards entry on Modernismo in the Bloomsbury Encyclopedia of Design, and to appreciate his work in context, see Victor Margolin's writing on Spain in the World History of Design.

Lucienne Day was a leading British textile designer. She was made Royal Designer for Industry in 1962 and became the first female Master of the Faculty of Royal Designers for Industry in 1987. Her abstract pattern-making brought modern elegance into the post-War British home, and her groundbreaking textile print 'Calyx' featured in the 1951 Festival of Britain. You can read more about Day's pioneering career in Francesca Baseby's short biography of her in the Bloomsbury Encyclopedia of Design, and for more information on her textile designs, see Jessica Kelly and Ness Wood's entry on Heal and Son.

Charles and Ray Eames were an American husband and wife design team who did much to define the aesthetics of postwar modernity, particularly in the United States, through the success of their plywood moulding system and various design projects. You can read more about the Eames' pioneering work in Robert Chester's overview of their careers in the Bloomsbury Encyclopedia of Design, or for detail on the various prizes their designs won, see the sections on design education and the role of designers in Victor Margolin's World History of Design.

In the chapter ‘Counterfeit Design’ in his book Deviant Design, Craig Martin explores the material world of designed goods and looks at how counterfeits function within social flows of production and consumption. Writing about manufacturing processes and cultures in different areas of the world for a range of products, from furniture to clothing and handbags, he examines the interrelationship between formal and informal understandings of design and design’s fundamental place in consumer culture. While addressing notions of illegality and the context of organized criminal activities, he highlights the critiques of copyright law, the ideologies of market exploitation and design’s complicity in the construction of inequality. He also sheds light on the creative innovation that can emerge from illicit designing and the wider debates around design’s radical potential. Otto von Busch’s chapter ‘Fashion Hacking’ in Design as Future-Making, edited by Susan Yelavich and Barbara Adams, also features a discussion of counterfeit goods and the evolving motivations for alternative making practices. This chapter looks particularly at hacking as a strategic and systematic practice from a fashion perspective, and how hacking can challenge ‘interpassive’ consumption. Short definitions of related terms can be found in The Bloomsbury Encyclopedia of Design, such as an article on 'Reproduction’ written by Alexis Comfort Holcombe, ‘Copy’ written by Gunnar Swanson and ‘Imitation’ written by Jeremy Ingham.

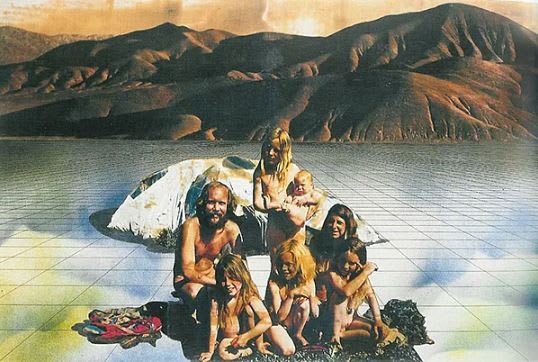

Paddy O’Shea gives an overview of Italian Radical Design in his article in The Bloomsbury Encyclopedia of Design, describing the mid-1960s avant-garde movement that focused on creating utopian environments. Catharine Rossi traces the trajectory of the second wave of the movement that flourished in the early 1970s in her essay ‘Crafting a Design Counterculture’, in Made in Italy: Rethinking a Century of Italian Design, edited by Grace Lees-Maffei and Kjetil Fallan, and draws comparisons between the approaches to design throughout both waves. Highlighting the ways in which collectives including Superstudio, Global Tools and Gruppo 9999 sought to overcome contemporary crises, Rossi examines design strategies that addressed a sense of alienation between humans and nature throughout the production, consumption and mediation of design, and that criticized the escalating commercialization of objects within the mainstream market. This chapter explores the crucial role of craft in the counterculture and how pastoral expression and an interest in handmade, pre-industrial design methods became key characteristics of the movement. Rossi also considers how Radical Design influenced modernist industrial values and the shifting perceptions of the movement throughout history.

As Siegfried Grönert describes in The Bloomsbury Encyclopedia of Design, Jugendstil was the name of Germany’s Art Nouveau movement at the turn of the 19th century. It was taken from the name of the art magazine Jugend (‘youth’), and was driven by a rejection of traditional academic and hierarchical art systems. Sabine Wieber sheds light on the women involved in the Jugendstil movement in her book Jugendstil Women and the Making of Modern Design. In the chapter Activists: The Elvira Photography Studio and Munich Feminist Politics, she writes about the artistic collaboration of Anita Augspurg (1857–1943) and Sophia Goudstikker (1865–1924), who broke away from conventional women’s roles to pursue professional careers, and how their photography studio in Munich, Hof-Atelier Elvira, became one of the most iconic and controversial Jugendstil buildings. The studio was designed by August Endell (1871-1925) in 1897 and featured an innovative aesthetic with ‘kelp-like’ exterior stucco work and ‘spider-web’ railings. As the women established themselves, they gradually became more involved in Germany’s women’s movement and moved among various political groups, and this chapter explores how the studio came to represent a space of radical ideas and intellectual debate. Charlotte Ashby gives an overview of the key ideas that shaped the international Art Nouveau movement in her lesson plan, which includes case studies and further reading. Tara Morton’s chapter in Suffrage and the Arts: Visual Culture, Politics and Enterprise, edited by Miranda Garrett and Zoë Thomas, looks at the political and artistic goals of another group that furthered debates around women’s work in the arts industry, the Suffrage Atelier, which was tied to the Arts and Crafts movement in early 20th-century London.

The Festival of Britain took place in 1951, with nationwide exhibitions dedicated to design, science, industry, farming and travel. Hundreds of designers and architects presented a modern vision for the future of Britain. The emblem was designed by graphic designer, Abram Games, for which, as described by Sarah Snaith in her article in The Bloomsbury Encyclopedia of Design, Games drew on his own personal philosophy, ‘maximum meaning, minimum means’. Harriet Atkinson explores the impact of the event in her book, The Festival of Britain, and the chapter ‘From the Planning of the Kitchen to the Planning of the Nation’ looks at how achievable solutions to issues related to housing, lighting, space and style were presented to the public. The festival was also a means of expressing a sense of family and ideas around what it meant to be British, and the planning incorporated extensive research into different aspects of society from a number of design teams. Exhibitions also included plans for the reconstruction of schools within communities, which Catherine Burke examines in depth in her chapter ‘Hidden Internationalisms’ in British Design, edited by Christopher Breward, Fiona Fisher and Ghislaine Wood.

In this chapter in her book, Modernism in Scandinavia, Charlotte Ashby provides a critical overview of aesthetic and ideological developments in art, architecture and design in Scandinavia during 1930-1950, highlighting some of the leading Modernist figures across Sweden, Norway, Finland, Iceland and Denmark. Good quality design for the broader population was a key focus during this period, after rapid industrialization and urbanization in previous decades. Ashby writes about the increasing occurrence of exhibitions as a way of influencing the general public and pays particular attention to the impact of the 1930 Stockholm Exhibition on the history of Swedish Modernism. In decades which saw an increased responsiveness to functionality and simplicity, Ashby notes the persistence of 19th-century craft ideals related to materials and skilled execution through new design initiatives. The chapter also explores key buildings of this period, highlighting the synthesis of National Romantic and Modernist influences in Reykjavik’s Church of Hallgrímur, the symbolic function of Oslo City Hall and its place in Norwegian cultural history, and the Bank of Finland murals and the promotion of public art.

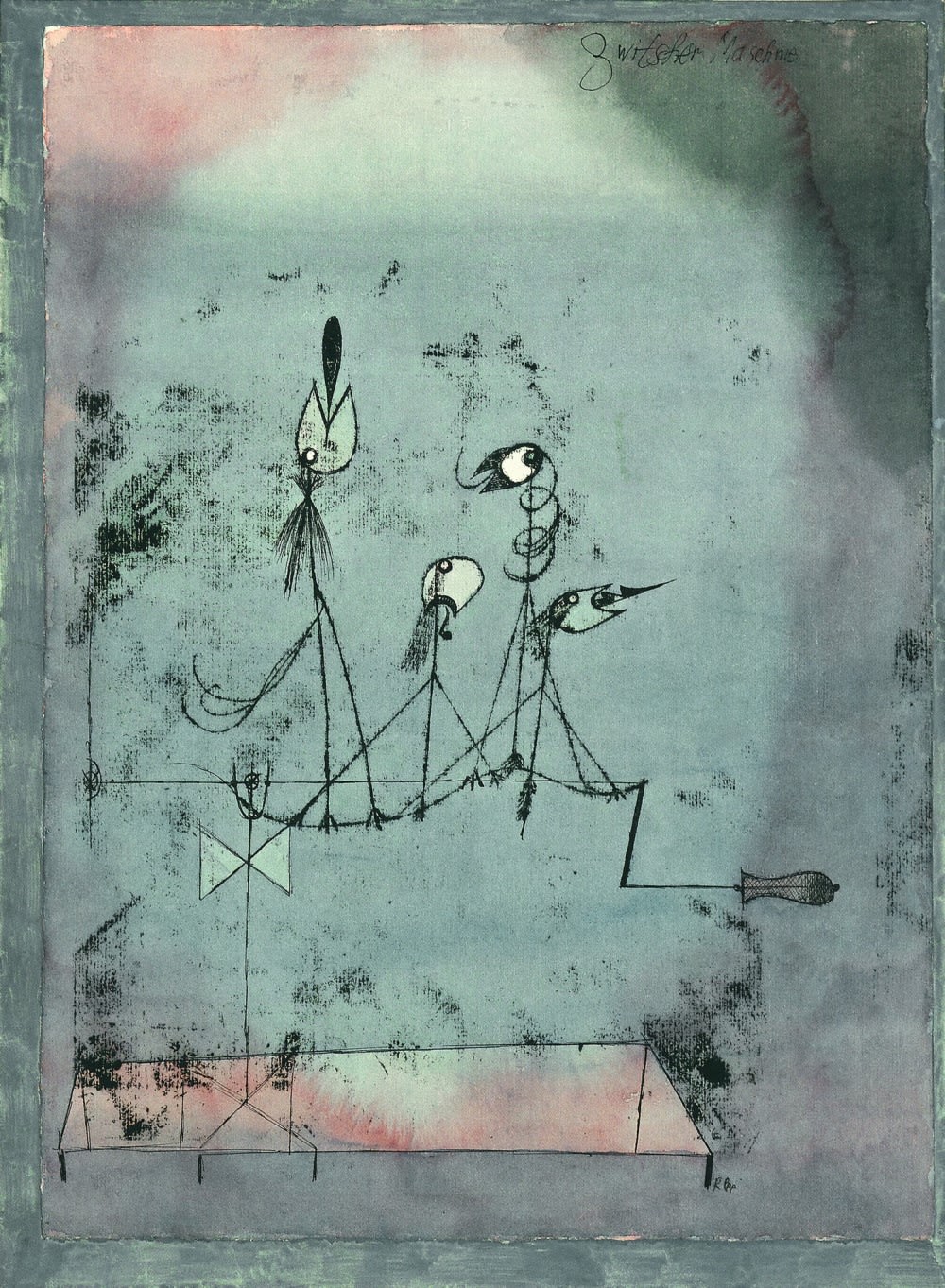

In his book, Color Theory, Aaron Fine writes about advances in color science throughout the 20th century and the use of color in what became known as ‘high modern’ art and design. Fine explores spiritual feeling around color and the introduction (and abandonment) of new color models, focusing particularly on the teachings of color theory among central figures at the Bauhaus school in Germany and the New York school of abstract expressionist painters. Examining the work and ideas of Josef and Anni Albers, Wassily Kandinsky, Paul Klee, Hanna Hoch and Giorgio De Chirico, Fine describes how developments within earlier competing art movements had enabled these artists to look anew at the use of color, to shake traditional, dogmatic approaches and to offer counter-narratives around modern ideas about color that influenced art, design and architecture.

A widely influential design publication in the USA during the mid-20th century was Russel and Mary Wright’s book, Guide to Easier Living (1950), which aimed to create and promote a specifically American design sensibility and offer an alternative to European Modernism. Lucinda Kaukas Havenhand analyses the influence of the publication, which outlined the Wrights’ ideas around domestic design and organization for a new way of life, and traces the trajectory of their impact on the industry in this chapter in her book, Mid-Century Modern Interiors. Elsewhere, in Screen Interiors, edited by Pat Kirkham and Sarah A. Lichtman, Marilyn Cohen provides a case study of mid-century interior decoration and material culture on screen in her chapter, ‘Furnishing I Love Lucy (1951-7)’. Cohen explores how the use of particular objects and furniture on the set of the popular 1950s US sitcom reflected developments in the modern, postwar home and how they aided the representation of domestic life in this era. Highlighting the role of furniture such as the space-saving drop-leaf table, in addition to changing styles and fabrics reflective of prosperity, and seating and positioning indicative of more informal living, Cohen demonstrates how furnishings on set were embedded in the portrayal of ideas related to identity and the political climate.

Yuko Hashimoto explores the rapid evolution of design organizations in Japan in her article in the Encyclopedia of East Asian Design, tracing the popularity and promotion of design as a profession in the mid-20th century. She examines key figures and groups, such as the Japan Industrial Designers’ Association (JIDA), and their aims to establish a Japanese design industry. D. J. Huppatz looks at the development of the professional status of design in postwar Japan, postcolonial Sri Lanka and colonial Hong Kong in this chapter in Modern Asian Design, by focusing on the careers of three influential practitioners: Kenji Ekuan, who founded GK Industrial Design Associates in Japan in 1952 and designed numerous products, ranging from a soy sauce bottle to a high-speed train; Minnette De Silva, the pioneering female architect in an overwhelmingly male domain in Sri Lanka, who employed a combination of rich traditional architecture and Modernist ideas; and the graphic designer, Kan Tai-Keung, whose ink paintings and refined visual language contributed to the evolution of Hong Kong’s design scene.

In 1981, Haig David-West examined the state of graphic design in Africa for the IX ICOGRADA General Assembly in Helsinki. His conference paper, in which he discusses the education, promotion, standardization and administration of graphic design in Africa towards the end of the 20th century, is republished as a chapter in Development, Globalization, Sustainability, Volume IV of Design: Critical and Primary Sources, edited by D. J. Huppatz. In The Bloomsbury Encyclopedia of Design, Donna Pido gives an overview of East African Design from the first to the 21st century, from settlement patterns and stitched boats in the Lamu Archipelago, to design streams in the 1800s and the dawn of the cyber age in the 1990s. Jeanne Van Eeden also writes about the role of design and the emergence of design ideologies, processes and practices in Botswana, Namibia, Zimbabwe and South Africa between 1850 and 2014 in her article on Southern African Design. For an insight into design movements in South Africa today, Luke Jordan writes about Grassroot, the non-profit technology start-up which provides tools for activists in his chapter, ‘Designing Tools for Low-income Community Organizing’ in Ethics in Design and Communication, edited by Laura Scherling and Andrew DeRosa.

In her chapter on African dress in Dress History, edited by Charlotte Nicklas and Annebella Pollen, Nicola Stylianou examines Ethiopian clothing and the acquisition of historic objects. Focusing particularly on clothing that belonged to Queen Woyzaro Terunesh, or Tiruwork Wube as she was also known, and drawing on deep archival research, Stylianou traces the clothing’s journey from Ethiopia to the Victoria and Albert Museum in the UK. Through these garments, she explores the history of Britain’s engagement with Africa and the shifting reception and status of African designed objects. In her chapter ‘La Mode Dakaroise’ in Fashion’s World Cities, edited by Christopher Breward and Davis Gilbert, Hudita Nura Mustafa explores the development and perception of Dakar as an African fashion capital. Reflecting on the 20th century characterization of Dakar as the ‘Paris of Africa’, Mustafa looks at fashion design and the economic and cultural conditions during the transformation of colonial cities. She addresses the interrelations of production, consumption and display in addition to the symbolic power of dress in a post-colonial fashion context.

In her chapter ‘Pleasure Craft’ in Radical Decadence, Julia Skelly discusses the different materials at play in the work of Mickalene Thomas, Nava Lubelski and Shary Boyle. In particular, Skelly examines how Mickalene Thomas, a contemporary Brooklyn-based mixed-media artist, explores ideas of femininity, beauty and race in her work. Contextualising Thomas’s work within the history of the Black female subject in visual and material culture, Skelly highlights her use of alluring, ‘excessive’ surface material, such as rhinestones, in her representations of Black women, and how particular materials can mask or disrupt viewers’ access to her subjects. Skelly also considers the use of materials that have traditionally been associated with craft in addition to the historical reception of women artists of color.

The Tokyo 2020 Olympics and Paralympics, postponed until summer 2021, will take place across forty-two venues as the Japanese capital hosts the Games for the second time. The organisers aim to promote unity in diversity, a vision that artist Asao Tokolo had in mind when designing the official emblem and athletes’ podium. He used ichimatsu patterns with different rectangular shapes to symbolise diversity and connection. His styling of traditional Japanese forms and patterns, as described by Hiroko Kurokawa in her chapter in the Encyclopedia of East Asian Design, is reflected in designer Ryo Taniguchi’s indigo blue and pink chequered Olympic and Paralympic mascots, Miraitowa and Someity. From traditional practices to new processes and modernization, Ritsuko Endo’s article in The Bloomsbury Encyclopedia of Design provides a comprehensive guide to the rich history of Japanese design from the 1800s until today.

The Tokyo 1964 Olympics were the first Olympics held in Asia and they had a transformative impact on design in Japan. The occasion initiated new building work, the development of commercial spaces, an increased demand for interior design and new graphic design enterprises. In ‘Modern Design in Japan (1957–1973)’, in the Encyclopedia of East Asian Design, Yasuko Suga traces design developments across post-war Japan and observes the 1964 Olympic designers’ shift from romanticized, pre-war imagery used in previous Games, towards fresh, high-tech visuals. Under the direction of art and design critic Masaru Katsumi (see Hiroko Shikita and Yasuko Suga’s article in The Bloomsbury Encyclopedia of Design), a team of designers including Yoshiro Yamashita, who designed the pictograms, and Yusaku Kamekura, who designed the posters, established a modern visual language. Paddy O’Shea also describes the contrast between pre- and post-war Olympic designs in his encyclopedia article and highlights the different ways in which designers undertake the task of communicating identity.

In the chapter ‘A Space of Pure Possibility’ in Picturing Socialism, author J. R. Jenkins explores the X. Weltfestspiele (10th World Festival Games) in East Berlin and its impact on public art. Taking place in 1973, 37 years after Hitler’s 1936 Olympics, the X. Weltfestspiele was seen as an opportunity to create a positive, politically progressive visual identity and to reinvent public space. Jenkins looks at the inspiration and ambition shared between the designers of the X. Weltfestspiele and the Munich Olympic Games in 1972, providing an in-depth look at the designs of Axel Bertram, Rolf Walter, Lutz Brandt and Otl Aicher. John Patrick Hartnett also gives an overview of Otl Aicher’s life and work in his article in The Bloomsbury Encyclopedia of Design.

Hosting the Olympics involves huge, rapid, urban transformations that can have devastating socio-spatial effects, and are often met with resistance. Jilly Traganou provides a critical overview of the history of anti-Olympic action in East Asia and the creative tactics employed by activists in her chapter, ‘Dissent by Design’, in The Encyclopedia of Asian Design, Volume Four: Transnational and Global Issues in Asian Design. Traganou examines design action involving subversive anti-campaign material, posters, symbolic appropriation, imagery and protest attire, in addition to designs generated through the Hangorin no Kai (No Olympics 2020) movement in Tokyo. Focusing on the Olympic Park in London, Chris Hay and Pat Brown look at the effects of the 2012 Games on local areas in their chapter, ‘Inside Out’, in Flow. Similarly, in Drawing Investigations, authors Sarah Casey and Gerry Davies highlight the work of artist Laura Oldfield Ford who, through the medium of drawing, investigates contested spaces in Britain’s towns and cities.

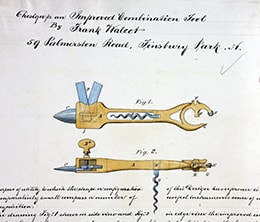

Combination tool (The National Archives)

For all the difficulties of self-isolation and social distancing, during the pandemic many people have been building, upcycling, painting and all things home-made. Whether practiced in order to combat boredom or stress, or to adapt to a new way of living, DIY has been increasingly popular. In his article in the Bloomsbury Encyclopedia of Design, Giuseppe Salvia looks at the history of DIY, covering the motivations and strategies for it, the challenges faced and the development of the practice over time. Within ‘Casting Things as Partners in Design’, her chapter in Relating to Things, Elissa Giaccardi discusses the potential of modern-day DIY and contemporary maker culture, exploring how technology has aided the revival of interest in self-made products.

The pandemic has also challenged our systems in society. Having encouraged designers to reconsider practices and collaborations with organizations, facilities and health services, there is an urge to think about design as a practice of care, explored by Laurene Vaughan in Designing Cultures of Care. Organizations also need to acknowledge the variety of needs and challenges faced by those working at home, as not everyone has access to an ideal workstation. In her contribution to Making Disability Modern, Jennifer Kaufmann-Buhler looks at office design and disability over the last few decades, exploring the politics and logistics of ergonomic design.

Valet chair (Designmusem Danmark: The Danish Chair exhibition)

Valet chair (Designmusem Danmark: The Danish Chair exhibition)

What does furniture mean to us and how do we engage with these designed objects in our homes? How do designers take this into consideration? In recent times, many of us may have been compelled to cast a creative eye on our homes and fill the space with meaningful objects. In his book Moving Objects, Damon Taylor explored the history of emotive design, examining the power of design and the relationships we have with objects that serve far more than functional purposes. Looking at the work of Droog designers like Jurgen Bey and Hella Jongerius, the Campana brothers, Marten Baas, Mathias Bengtsson and others, Taylor explores contemporary issues of how we live with objects in our homes and what design can really do. He also addresses how and why we ascribe value to certain objects in 'Valuing Emotive Design', particularly how the emotional influence of an object can relate to its value. But how do we value design after a pandemic? How do we now value objects, people, labour, environments, and systems? The pandemic has forced us to reassess our ideas about what we value, what moves us and what we should cherish moving forward.

In her chapter in Designing the French Interior: The Modern Home and Mass Media, Fae Brauer explores how the bedroom in fin-de-siècle France came to be seen as a sanctuary from the stressful conditions of the metropolitan city, but also as a site of psychological self-exploration, self-projection, and self-fashioning.

In 1920s Japan, the home became the site for a modernization program sponsored by the Japanese government. In his book Modern Asian Design, D.J. Huppatz describes how Japanese citizens were encouraged to shun traditional living practices and organization of space in favor of ‘a modern home centered on the nuclear (rather than extended) family, and on design principles such as functionality, simplicity, and efficiency.’ In place of the flexible, minimal spaces of a traditional Japanese interior, this Westernized home featured partitioned rooms with discrete functions and fixed furniture.

Home can also be a site to display individual taste through design choices. In her book Retro Style, Sarah Elsie Baker interviews ‘retro enthusiasts’ about the meanings and values represented by domestic furniture and decorative objects.

Sometimes home can have more uneasy connotations. In The Architecture of David Lynch Richard Martin writes: ‘In Lynch’s films, images of home hold immense power. A single shot of Henry’s apartment in Eraserhead, the Palmer residence in Fire Walk With Me or the Madison house in Lost Highway is enough to induce rich associations… For Lynch, our most familiar surroundings inevitably contain unhomely elements. Home, he contends, is “a place where things can go wrong.”’

This is the first comprehensive publication to focus on East Asian design and its histories. Although definitions of design in Asia are multiple, fluid, and historically contingent, the disparate cultures within this vast landmass have long produced arts and crafts, interior, graphic, and design objects for domestic, regional and global consumption. The encyclopedia provides in-depth, critically informed coverage of these practices, products, and the interpretive issues pertaining to them. The work is organised by country to reflect specific regional and national histories and geographies. Within these geographies, traditions, histories, theories, and practices as well as key issues in modern and contemporary design are considered. The topics covered in this volume range from ceramics, textiles and interiors to architectural, environmental and sustainable design. You can read the introduction to this volume here.

This important new area of design academia addresses the moral complexity of designed objects and systems. Guns, for instance, are created by designers. What is the correct ethical framework for such a designer to work within? Euthanasia - although an experience rather than an object - is a similarly controversial designed thing. In their edited collection Tricky Design, Tom Fisher and Lorraine Gamman explore the moral complexities which design can in turn both help and hinder.

The definition of a 'designed object' has changed vastly in recent years. Thus, phones, laptops and fitness trackers do not take a purely physical form - they are networked, dynamic, and often capable of learning from us just as much as we - their users - are from them. This transformation in the meaning of 'designed objects' led Johan Redström and Heather Wiltse to produce their new title Changing Things. In it they address critical questions which have assumed a fresh urgency in the context of these rapidly developing forms, and they propose a radical new system for understanding and relating to objects.

Many, although not all, women students at the Bauhaus were apprenticed in the weaving workshops, where makers such as Anni Albers developed techniques that were both formally and artistically innovative. In their study of women at the Bauhaus, Patrick Rössler and Anke Blümm reveal how women also made an important contribution in a range of areas including photography, printmaking, drawing, and even in the male-dominated field of architecture.

The films of the legendary director Stanley Kubrick are testament to his holistic and perfectionist approach, and throughout his career, he collaborated with key figures from the worlds of fashion, production and graphic design to create unforgettable cinematic spectacles. The production designer Ken Adam created both the NORAD control room in Dr Strangelove (1964) and the loving recreation of eighteenth-century England of Barry Lyndon (1975). Saul Bass designed the opening and closing sequences of Kubrick's Spartacus (1960) and the film poster for The Shining (1980). Read Pat Kirkham's account of Saul and his partner Elaine Bass's work in film design, and how Bass's background in graphic design for advertising influenced his distinctive use of striking symbols, modern typography and hand lettering. Kubrick's totalising vision and attention to detail is evident in his 1968 masterpiece 2001: A Space Odyssey, on which Kubrick collaborated with production designer Anthony Masters and art director Ernest Archer, from the stunning sets of the spaceship USS Discovery One down to the cutlery used by its astronauts, which was designed by Arne Jacobsen for the restaurant of the SAS Royal Hotel in Copenhagen.

The Bloomsbury Design Library features a range of books and articles which consider the relationship between design and wellbeing. Gretchen C. Rinnert's 'Designing for a Better Patient Experience' showcases how designing better doctor-patient communication can mitigate unnecessary anxiety and discomfort for hospital patients, while Jonathan Chapman's 'Emotionally Sustaining Design' explores the way in which designed objects inspire and alter our emotions, sometimes radically. The Bloomsbury Encyclopedia of Design also features a range of relevant articles; see the entries on care, comfort, health and safety design and healthcare design.

Elizabeth Resnick's Developing Citizen Designers sets out to empower students, educators and designers in the early stages of their careers to learn and practise design in a socially responsible manner. Developing Citizen Designers is a practically and pedagogically focused book, with each chapter addressing a particular area or issue within design practice and education, with an overview framing essay, interviews with practitioners and educators, and assignment briefs through which the reader can understand the process by which a design project is briefed, developed, and the outcomes assessed.

Bloomsbury Design Library features a wealth of scholarship on Scandinavian design. Charlotte Ashby's Modernism in Scandinavia and Kjetil Fallan's Scandinavian Design both provide critical overviews of the region and its designerly output as a whole, focusing on the eventful twentieth century. Mark Mussari's Danish Modern focuses on Denmark between the pivotal years 1930-1960 and Sara Kristoffersson's Design by IKEA explores the style and influence of the internationally renowned Swedish brand.

The Bloomsbury Design Library features an impressive range of texts relating to the theme of play. You can read about the Swedish toy manufacturer Brio, Mattel, the US company which created Barbie and various iconic toys and brands, including Rubik's cubes and Hello Kitty. The notion of toys such as dolls and soldiers enforcing particular gendered roles is now widespread - you can read about this in Kate Hepworth's fascinating article on gender and design objects in the Bloomsbury Encyclopedia of Design.

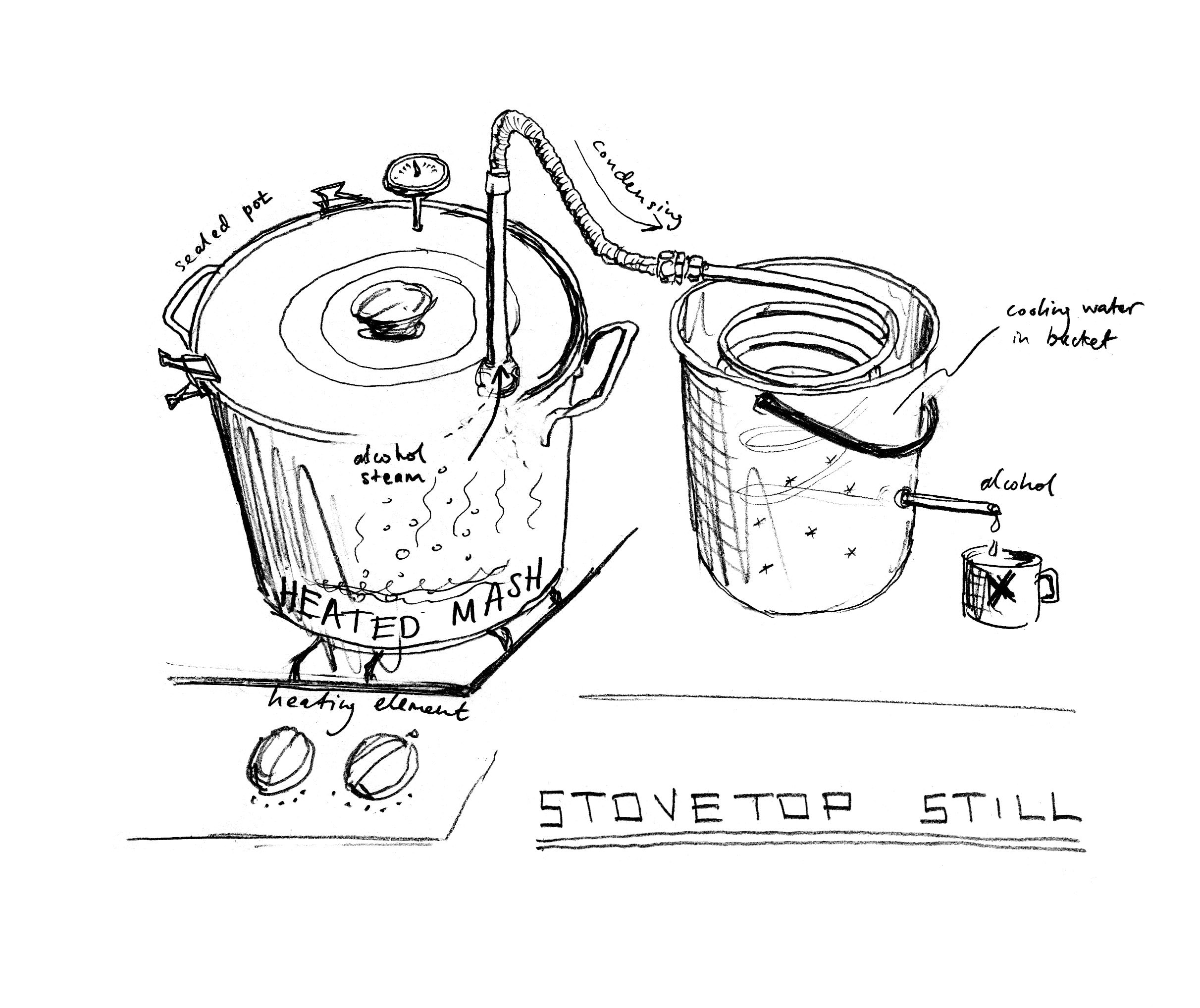

As Otto von Busch writes in his book Making Trouble: Design and Material Activism, ‘someone’s misuse is useful to another’. In the chapter ‘Brewing Dissent’ he explores the power and agency that can be found through primitive making by looking particularly at homebrewing machinery, alongside the long history of alcohol production and its policing. While seemingly a small act of mischief to some, producing alcohol at home was a material form of independence and autonomy under colonial rule for others, and von Busch provides an insight into how a simple domestic object was mobilized in social conflict to disrupt the order of things. He describes the skills and processes involved in distilling alcohol and the design elements of a machine, and focuses on the empty chamber in which alcohol and dissent could brew at the same time. For the context of the contemporary design workshop, he introduces ways to think creatively about material agency and the power infused in making primitive objects.

The Citroën 2CV, or ‘Deux Chevaux’ (two horses) model, was introduced in 1948 and became one of France’s most successful cars. Simply constructed and affordable to buy and maintain, it was popular with France’s rural workers, with its enhanced suspension and small size allowing easier travel across farm tracks and unpaved roads, and through the narrow streets of towns and villages. Kjetil Fallan gives an overview of popular ‘people’s cars’ and their domestication in the chapter ‘Theory and Methodology’ in his book, Design History, and notes that the Citroën 2CV, designed to be able to safely transport a basket of eggs across a ploughed field, became a symbol of a European response to oversized and overdesigned American cars of the period. The Citroën company was initially established as an arms factory in 1919 by the French manufacturer, André Citroën (1878–1935), and then began producing cars after World War I. Paddy O’Shea writes about the founder in his article in The Bloomsbury Encyclopedia of Design and describes the company’s liberal ideas and aims for social mobility in the early years. As highlighted by Martina D’Amato in her encyclopedia article, the Citroën 2CV was produced until 1990, sold more than five million units, and competed with other popular cars of the time aimed at working class families, such as the Volkswagen Beetle and the Renault 4CV.

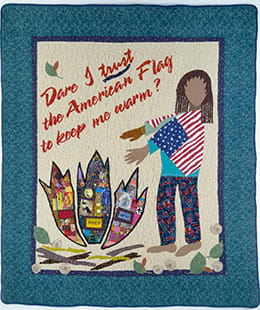

Patriotic Quilt (1995) was made by Kyra E. Hicks, a quilt artist and historian known for creating story quilts which explore personal and political themes. Hicks juxtaposes words and images to create personal, beautiful and thought-provoking compositions. This particular cotton quilt depicts a Black woman being warmed by the American flag whilst the names of three prominent African-American women – Joycelyn Elders, Lani Guiner and Anita Hill – burn in flames alongside other American symbols. Elders was the Surgeon General of the United States from 1993-1994 and was forced to resign when her advocacy for comprehensive sex education was seen as controversial. Guinier, a civil rights theorist, was President Bill Clinton’s nominee for Assistant Attorney General for Civil Rights in 1993, yet lost his support due to negative press around her writing. In 1991, Hill spoke out about alleged sexual harassment by the Supreme Court nominee Clarence Thomas. Hill was subsequently demonized by the media and the United States Senate affirmed Thomas’s appointment. Describing Patriotic Quilt, Hicks said that the provocative work asks how much a woman of color may trust the USA government. As highlighted by Magali An Berthon in her article on quilting in The Bloomsbury Encyclopedia of Design, since the late twentieth century, the craft of quilting has often been used to explore and critique ideas around women and work. Catherine Harper writes about other quilts which have social, political and emotional significance in her chapter, ‘Sex, Birth and Nurture Unto Death’ in Love Objects, edited by Anna Moran and Sorcha O’Brien. She discusses quilts such as the NAMES Project AIDS Memorial Quilt, an ongoing project, as well as historical contexts of quilting and the readability of cloth.

As Raiford Guins describes in his book, Atari Design, Pong was not just a new amusement product designed for an existing market. Innovative cabinet design was key to the success of the table-tennis themed arcade game, a success that shaped a brand, an industry, and spawned an incredible number of clone machines throughout the 1970s. Guins explores how Atari developed their products for new, diverse environments such as restaurants, department stores, country clubs, game rooms and airports, and they even installed machines throughout the Olympic Villages during the Los Angeles Olympics in 1984. Considering shape, materials, form and design, and the contributions of industrial designers including Regan Cheng and Peter Takaichi, Guins looks at how Pong shaped a new gaming experience in the late 20th century.

Originally marketed as the Marshmallow love seat #5670, the Marshmallow sofa was designed by Irving Harper at George Nelson Associates’s New York City studio and manufactured by Herman Miller. The sofa’s playful design features 18 circular ‘marshmallow’ cushions, which can be covered in fabric, vinyl or leather in bright colors, arranged over a metal frame, in such a way that they appear to float on air. For sale from 1956 until the mid-1960s, the sofa was revived as part of the Herman Miller Classics range and continues in production today.

From record-breaking bullet trains to beautiful Buddhist temples and kimono, Japan is a country with a rich and diverse design tradition. The Encyclopedia of East Asian Design features 39 articles addressing the history of Japanese crafts and design, from pre-modern times to the 21st century, covering aesthetics, colour and pattern, calligraphy, ceramics, metalwork, architecture, interactive design, and much more. Read Ellis Tinios and Christine Guth’s article on printing in pre-modern Japan, and Hiroshi Narumi’s overview of contemporary Japanese popular culture.

Hong Kong-born American designer Izabel Lam created her silver-plated sphere cutlery range in 1990. Lam is known for designing, producing, and selling contemporary dinnerware, cutlery, and tabletop accessories. Her range aims to satisfy 'the challenge of the compromise of creativity and commerce' and her creations 'encompass the nuances of material and movement, the perfection of imperfection, function with attention to detail, and simplicity molded by the human touch'.

The Danish Chair tells the story of how Danish design turned into an international mega-brand, and draws a picture of the 20th-century Danish success story and export adventure known as Danish Modern. The chair is the closest item of furniture to a human being. It affects and reflects the body it has to carry with arms, legs, a seat and a back. It is the acid test of designers and a favourite object of design historians. The chair is also one of the most culture-bearing design objects. It reveals everything about the age and the society in which it was created. It invests the person sitting in it with status and identity. Discover a myriad of chairs in this unique exhibition.

Passports are small but powerful designed objects. In his study The Design Politics of the Passport, Mahmoud Keshavarz reveals the social, political and material practices associated to the passport. Combining design studies with ethnographic research among undocumented migrants and passport forgers, Keshavarz shows how the world is designed to be strikingly open and hospitable to some, yet highly confined and demarcated for others. He also demonstrates how those who are affected by such injustices dissent from their situation through the same capacity of design and artifice.

The famous architectural toy Lego derives its name from the Danish phrase 'leg godt' meaning 'play well', and is manufactured by the eponymous Danish company The Lego Group. First put on sale in 1932, the toy went through several early reinventions. Perhaps the most significant of these was in the late 1940s. In 1947 Lego's creator Ole Kirk Christiansen bought the first injection-molding machine in Denmark and two years later starting using it to produce his bricks. This use of innovative technology propelled Lego on its way to becoming the internationally recognised brand it is today.

The 'Welcome Home' project - as featured in Developing Citizen Designers - provides an example of how design can be used to improve wellbeing. Professor Lisa Rosowsky and a group of graphic design students at the Massachusetts College of Art and Design were tasked with designing a booklet to help new tenants moving into new 'green' housing developments feel comfortable and safe in their accommodation, and to encourage them to live more sustainably. The information was presented in a highly visual way to cater for different levels of literacy, and was written in both English and Spanish to improve its accessibility. The project was an unqualified success and the booklet has been in print since 2011.

The Bauhaus was an avant-garde school of design and architecture founded in Germany in 1919, hugely influential in the fourteen years before it was forced to close by the Nazi regime. The school's pedagogical approach was based on workshops, in which students received training in a wide range of applied arts disciplines. The Bauhaus became associated with a modernist aesthetic in which form and function were equally valued, and with a utopian project to transform society by design. Clive Edwards' bibliographic guide and lesson plan provide useful resources to learning and teaching about the Bauhaus.

Through our featured lesson plan and bibliographic guide on Scandinavian modernism, students can learn about the importance of national style to European modernisms, the commercialisation of Swedish design, and the concept of 'design heroes' such as Alvar Aalto and Arne Jacobsen.